Svadhyaya: The Study of the Self and Inner Nature

Since the dawn of civilization, human beings have sought to understand themselves. Across ancient cultures and spiritual traditions, numerous schools of thought have emerged—each offering its own definition of self-knowledge and laying out distinct paths toward discovering the truth of our existence. It is as though each school has gazed upon the same precious gem from a unique perspective, attempting to reveal its essence.

Despite their differences, all these traditions ultimately seek one aim: to uncover the jewel of the human soul. Yoga, too, offers a profound and detailed pathway to self-realization.

Within the teachings of yoga, a central pillar known as Svadhyaya—meaning self-study or the study of one’s nature—emphasizes that self-knowledge not only enriches the quality of life but also provides the essential foundation for material and spiritual growth. In other words, to know oneself is to unlock the mysteries and patterns of the universe. Through this knowledge, we begin to awaken latent abilities and discover the deeper meaning of life.

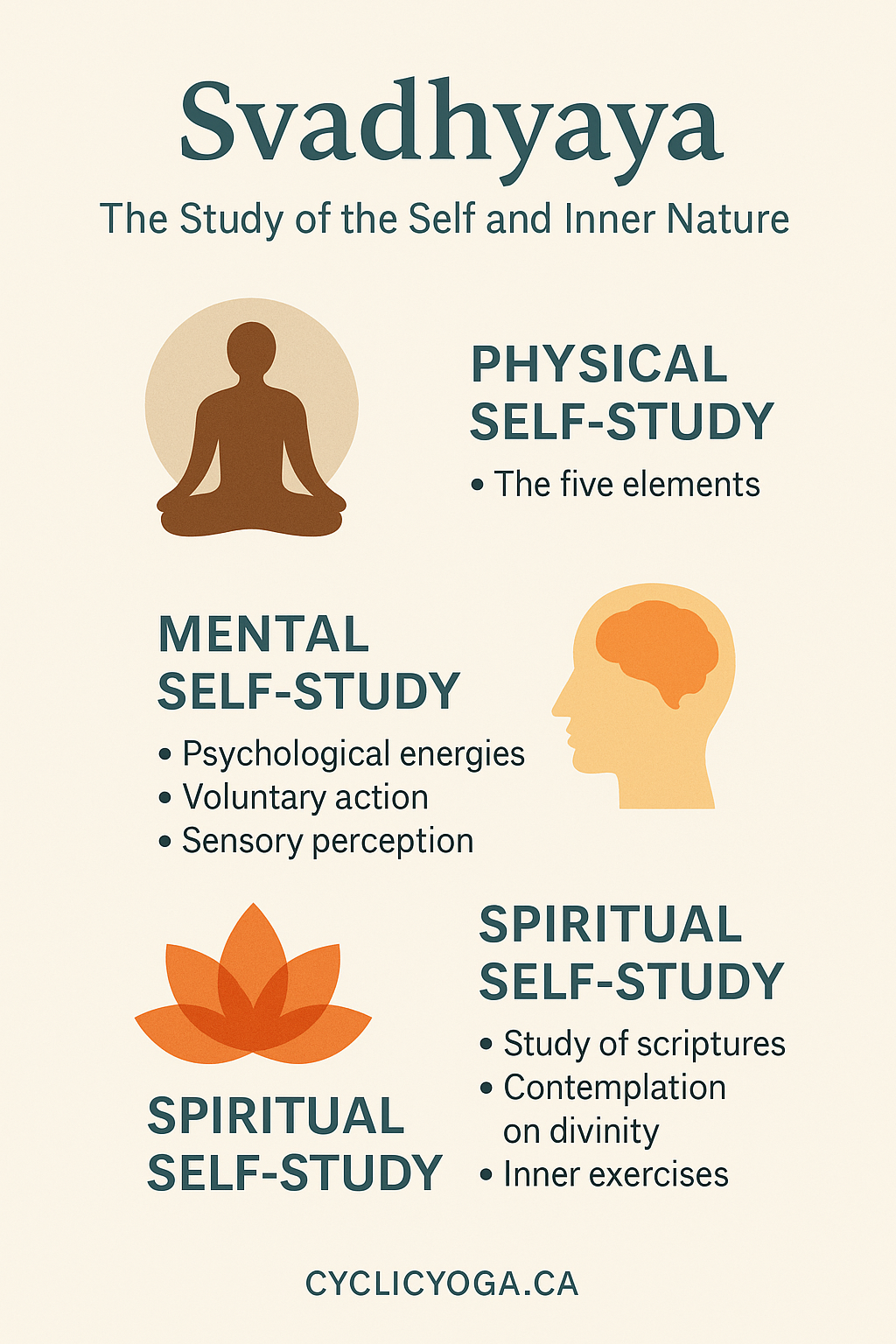

The “self” is composed of multiple layers, each holding immense potential. In yoga, the study of self is structured into three interwoven domains:

1. Physical Self-Study (Sharira Svadhyaya)

From the yogic perspective, the physical world is composed of five fundamental elements. All material forms are combinations of these elements, but the proportions vary in each individual—shaping our physical and psychological characteristics, known as doshas or constitutions.

The five elements are:

Earth (Prithvi) – Found in bones, muscles, skin, hair, nails, and other solid parts.

Water (Apas) – Present in blood, lymph, synovial fluid, sexual secretions, and hormones.

Air (Vayu) – Manifested as the breath and motion within the body.

Fire (Agni) – The source of body heat and metabolic functions.

Ether (Akasha) – The space within the body and between organs, and the space our body occupies within the cosmos.

These elements operate under the laws of time, space, and gravity, undergoing changes like growth, decay, and dissolution. The unique blend of elements in each person creates their prakriti, or personal constitution, categorized as:

Vata (Air + Ether) – Creative and energetic, yet prone to anxiety and dryness.

Pitta (Fire + Water) – Intelligent and focused, yet prone to anger and inflammation.

Kapha (Earth + Water) – Stable and compassionate, yet prone to sluggishness and attachment.

Understanding our constitution and elemental balance is essential for maintaining health and preventing disease. A healthy body is the fertile soil in which both material and spiritual growth can flourish.

2. Mental Self-Study (Manas Svadhyaya)

The mind, in yogic science, is a field of dynamic psychological energies. Formed and shaped through learning and environmental conditioning, it is the seat of cognition, emotion, and awareness. Yoga describes 19 subtle elements of the mind, divided into four functional groups:

A. Voluntary Action (Karma Indriyas)

These govern intentional biological activities:

Vak – Speech

Pani – Grasping (Hands)

Pada – Movement (Feet)

Upastha – Reproduction (Genitals)

Payu – Elimination (Anus)

B. Sensory Perception (Jnana Indriyas)

These are our tools for learning through the five senses:

Shrotra – Hearing (Ears)

Tvak/Tvacha – Touch (Skin)

Chakshu – Sight (Eyes)

Jihva – Taste (Tongue)

Ghrana – Smell (Nose)

C. Vital Energies (Pranas)

Responsible for involuntary physiological functions:

Udana – Head and upward movement

Prana – Chest and respiratory system

Samana – Digestive system

Apana – Pelvic and elimination processes

Vyana – Circulation throughout limbs

D. Cognitive Faculties (Antahkarana)

These govern identity, intellect, and awareness:

Manas – The lower mind (processing)

Buddhi – Discriminative intelligence

Ahamkara – Ego or sense of “I”

Chitta – Consciousness and memory

These 19 components collectively form what is called the subtle body (sukshma sharira). Every action—mental or physical—is processed through these faculties and stored as karmic impressions. The soul (atman), transcending both mind and body, acts as the observer and witness of all these activities—a conscious presence beyond form.

In yoga, the chakras—energy centers within the subtle body—are where body, mind, and spirit intersect. Moving through the chakras in self-study awakens deeper levels of awareness and transformation.

3. Spiritual Self-Study (Atma Svadhyaya)

The spiritual aspect of human existence is what sets us apart from all other beings. It brings depth, direction, and sacredness to life. As we evolve spiritually, noble qualities such as faith, compassion, and wisdom become more apparent in our daily lives.

Spiritual self-inquiry awakens us to our divine origin and helps us realign with our soul’s purpose. In the spiritual dimension of Svadhyaya, three key practices are emphasized:

Study of ancient scriptures – To understand the wisdom traditions that illuminate the soul’s journey.

Contemplation on divinity – To connect with the universal intelligence and the nature of the Divine.

Practical inner exercises – To directly experience one’s essence and attain self-realization.

Svadhyaya is not merely an intellectual pursuit. It is a lived, experiential process that helps us shed false identities, rediscover our essence, and find alignment with the cosmos. Through body, mind, and spirit, self-knowledge leads us home—to our true Self.